reposted from 10-20-2015

John is not a direct ancestor of ours, but he was a first cousin of once removed of Robert Luttrell and therefore the 2nd cousin (thrice removed) of our John Daniel Littrell).

John is not a direct ancestor of ours, but he was a first cousin of once removed of Robert Luttrell and therefore the 2nd cousin (thrice removed) of our John Daniel Littrell).

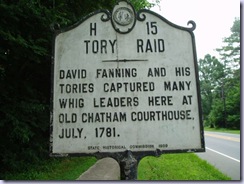

As mentioned in a previous article I was unable to locate the actual Battle Field that Col. John Luttrell had died on, but had found the current location of Lindley Mills and one marker referencing the battle.

I have located the actual location online and the following is from that website:

"On September 13, 1781, the largest engagement of North Carolina’s “Tory War” took place near Thomas Lindley’s mill. In the aftermath of Lord Charles Cornwallis’s invasion of North Carolina in the spring of 1781, a prolonged civil conflict erupted in the Piedmont. With no regular forces actively campaigning in the area, Whig and Loyalist militias openly attacked each other as well as neutral parties. Loyalist Colonel David Fanning, leader of the Loyalist militia in central North Carolina, had received approval from British authorities in Wilmington to attack the state capital at Hillsborough. Fanning led 435 Loyalists from central and western North Carolina. He had been reinforced by two small bands of Tories from Cumberland and Bladen counties led by Colonels Archibald McDougald and Hector McNeil, raising his overall force to nearly 700 men.

At dawn on September 12, 1781, under the cover of a heavy fog, Fanning’s men brazenly entered Hillsborough, taking the town by surprise and capturing 200 prisoners, including most of the General Assembly and Governor Thomas Burke. Having thoroughly plundered the village, Fanning and his men, their prisoners in tow, departed for Wilmington in the afternoon.

Word of the disaster reached Brigadier General John Butler of the North Carolina militia that evening. Butler, who had led North Carolina militia at Guilford Courthouse, quickly organized men from Orange County to intercept the Tory force. Accounts differ on how many men Butler raised, but a 350-man force is the best estimate. His second-in-command was Colonel Robert Mebane, a Continental army veteran. Another Continental army veteran, Captain Joshua Hadley, arrived that evening with a small company of Whigs from Cross Creek, augmenting Butler’s force to nearly 400 men.

Butler’s men arrived ahead of Fanning at Lindley’s Mill, near a ford across Cane Creek on a plateau overlooking Stafford’s Branch. On the morning of September 13, as the Loyalists crossed, a musket volley from the tree line on the opposite bank tore into their ranks. At first the Loyalists balked, and Colonel McNeil ordered a retreat, but was rebuked by Colonel McDougald who accused him of cowardice. McNeil, infuriated by the remark, instead led a charge toward the Whig position but was immediately cut down by rifle fire and killed.

Hearing the gunfire at the head of the column, Fanning rode to the front, ordering the prisoners to be housed in the Spring Friends Meeting House in the rear. Although outnumbered, Whigs pressed the head of the Tory column back toward the chapel, apparently intent on freeing Burke and the other captives. Fanning then organized an assault that flanked Butler’s men, threatening to surround his forces. Just as he began driving Butler’s men from the field, Fanning received a serious wound in his arm that shattered the bone and severed an artery. He left the column in McDougald’s command and retired from the field. Pressed on both front and flank, Butler retreated, and Fanning’s column continued on to Wilmington with the prisoners.

That night, local Quakers collected the dead and wounded on the field. Whig casualties consisted of 25 killed, 90 wounded and 10 captured, while the Tories lost 27 killed and 90 wounded. Surgeons from the surrounding countryside were called upon to help administer to the wounded. Among them was Dr. John Pyle, who earlier that year had led his Loyalist militia regiment into an ambush at Pyle’s Defeat. Putting aside his earlier allegiances, Pyle worked tirelessly for the injured of both sides. In return, Governor Alexander Martin pardoned him at war’s end."

To place the above information in Context to Col. Luttrell the Reverend Caruthers describes the death of Colonel John Littrell and the battle:

"Several of the highest officers on both sides were killed and nearly an equal number of each. These were men of much merit as officers, and their death was a great loss to their respective parties. On the Whig [American] side Major John Nalls and Colonel Lutteral were among the slain...."

"...Colonel Lutteral was also killed about the close of the battle and was a great loss to the country. He is said to have been a brave and valuable officer; but his men thought him too severe in his discipline… Having advanced at the head of his men within pistol shot of a Tory from Randolph, by the name of Rains, who was in the act of loading his rifle, and fired at him with his pistol but without effect. He then wheeled his horse and dashed off, to get out of reach before the other would be ready to fire; but Rains, having finished in time, leveled his gun at him, when at full speed, and shot him through the body. He did not fall but rode to a house about half a mile distant, where the good people took him upstairs and furnished him with a bed and every comfort in their power. While lying there bleeding and dying, he dipped his finger in his own blood and wrote his name upon the wall. The house stood there as a Monument of the Cane Creek Battle and of Colonel Lutteral's death until about seven or eight years ago; and the Colonel's name retained its color and brilliance until the last. There were two men belonging to Fanning's troop by the name of John Rains, father and son, and McBride says that John Rains, SR., was killed at the battle of Cane creek…"

sources:

- LITTRELL and LUTTRELL HEROES In the WAR for American Independence [All Spellings]: By KARL DEWITT LITTRELL [decsd] with NANCY LITTRELL GOLDSBERRY

- Patrick O’Kelley, Nothing But Blood and Slaughter (2004), III

- Algie I. Newlin, The Battle of Lindley’s Mill (1975)

- William S. Powell, ed., Encyclopedia of North Carolina (2006)

- Eli Caruthers, Revolutionary Incidents and Sketches of Character, Chiefly in North Carolina (1854)

- http://www.ncmarkers.com/Results.aspx?ct=ddl&k=Keywords&sv1=Keywords&sv2=Revolution

The above information is from: Military Role Call: The Littrell Family of Mississippi County, Missouri, The Littrell Family Journals Volume IV. (click here)

also: Littrell Family Veterans Video

999/1311